Project Gutenberg's Jack Harkaway in New York, by Bracebridge Hemyng

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most

other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions

whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of

the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at

www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have

to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook.

Title: Jack Harkaway in New York

or, The Adventures of the Travelers' Club

Author: Bracebridge Hemyng

Release Date: August 15, 2014 [EBook #46588]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK JACK HARKAWAY IN NEW YORK ***

Produced by Demian Katz, E. M. Sanchez-Saavedra, Joseph

Rainone and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at

http://www.pgdp.net

| $2.50 a year. | Copyrighted in 1879 by Beadle and Adams. | July 1, 1879. | ||

| Vol. IV. | Single Number. |

PUBLISHED WEEKLY BY BEADLE AND ADAMS, No. 98 WILLIAM STREET, NEW YORK. |

Price, 5 Cents. |

No. 101. |

OR,

The Adventures of the Travelers' Club.

BY BRACEBRIDGE HEMYNG,

(Jack Harkaway,)

AUTHOR OF "CAPTAIN OF THE CLUB," "DICK

DIMITY," ETC., ETC.

CHAPTER I. A SPECIAL MEETING OF THE TRAVELERS' CLUB.

CHAPTER II. "THE DUEL ON THE SANDS."

CHAPTER III. THE ASSASSIN AT WORK.

CHAPTER IV. ADÉLE.

CHAPTER V. THE VOYAGE.

CHAPTER VI. THE ABANDONED SHIP.

CHAPTER VII. THE MYSTERY OF THE DESERTED VESSEL.

CHAPTER VIII. A LOVERS' QUARREL.

CHAPTER IX. THE RACE.

CHAPTER X. A RECONCILIATION.

CHAPTER XI. FORTUNE-TELLING.

CHAPTER XII. MRS. VAN HOOSEN SACRIFICES HER DAUGHTER TO HER AMBITION.

CHAPTER XIII. "A BUFFALO-HUNT."

CHAPTER XIV. MASTER AND SLAVE.

CHAPTER XV. MR. MOLE PLAYS BASE-BALL.

CHAPTER XVI. BAMBINO IN THE HOSPITAL.

CHAPTER XVII. JACK MAKES A LAST APPEAL.

CHAPTER XVIII. THE BRIDAL.

A SPECIAL MEETING OF THE TRAVELERS' CLUB.

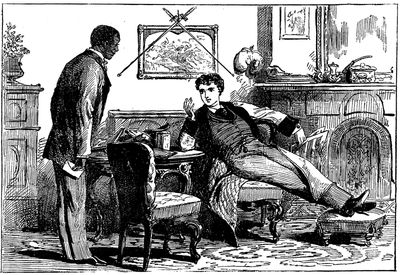

"'Pears to me, Marse Jack, you done gone been quiet long 'nuff dis spell," exclaimed Monday, Jack Harkaway's colored servant, as he entered his master's room at the hotel.

It was a fine morning in the month of October.

Jack Harkaway at the age of eighteen, well supplied with money, had been leading an idle life in London for some time.

This did not suit Monday's ideas at all.

Looking up from the newspaper he was reading, Jack pushed back his curly hair from his ample forehead and smiled.

"What would you like to be doing, my sable friend?" he asked.

"Don't know 'zactly that I'd like to do anything in pertickler, Marse Jack, but dis chile hasn't killed nobody lately."

"You must learn to curb your savage instincts, Monday," said Harkaway. "But this I may tell you. It is possible that we shall be on the move sooner than you expect."

"Hooray! Golly, sah, dat's de good news, for suah. I'se been afraid I'se gwine ter rust out, 'stead ob wear out."

"What have you got in your hand?"

"Ki! What hab I got? A letter. I misremember dat I come in for somet'ing."

"Give it me."

Monday handed his master a letter and retired, without venturing on any further remark.

The epistle was directed in a delicate lady's hand and was highly perfumed.

Breaking the seal, Jack muttered: "From Lena Van Hoosen. Wants to see me at once. Something important to communicate. I'll go in half an hour. Lucky it was not this evening, as I have a special meeting of the Travelers' Club to attend."

Miss Lena Van Hoosen belonged to one of the first families of New York city, and at nineteen years of age was the prettiest and most accomplished girl in London, which is saying a great deal.

"'PEARS TO ME, MARSE JACK, YOU DONE GONE BEEN QUIET LONG 'NUFF DIS SPELL," EXCLAIMED MONDAY, JACK HARKAWAY'S COLORED SERVANT, AS HE ENTERED HIS MASTER'S ROOM.

She had been making the tour of Europe with her mother and father, and was resting awhile, before returning to America. Jack had been considerably struck with her grace and beauty, paying her much attention, since his first introduction to her at a ball.

He had every reason to believe that she also thought very well of him.

Taking up his hat, he quitted the hotel, and hiring a cab, was driven to Miss Van Hoosen's residence in Belgravia.

She received him cordially.

"I sent for you, Mr. Harkaway, for a particular reason," she exclaimed.

"Indeed!" replied Jack. "Whatever the reason may be, I feel very much indebted to you for this mark of attention on your part."

"In the first place, we are going home next week."

"So soon?"

"Yes, papa has business to attend to and we have already been absent nearly twelve months."

"I regret that I shall lose your agreeable society."

"The gap in the circle of your acquaintance, which our going away will create," said Miss Van Hoosen, "I have no doubt you will soon supply."

"Not so easily as you imagine," he answered.

"But that is not all I wanted to see you about," continued Miss Van Hoosen as her face assumed a graver expression. "You are well acquainted with Lord Maltravers."

"Yes, his lordship is a member of the same club as myself—the Travelers'. I have no reason to believe that he likes me; in fact, a coldness has always existed between us."

The young lady drew her chair closer to Jack.

"Now," she said, "what I am going to tell you, must be received in strict confidence."

"Certainly, if you wish it."

"Yesterday, Lord Maltravers called upon me and did me the honor to ask for my hand."

Jack's heart fluttered a little, for this was more than he had ever dared to do.

"What answer did you give him?" he inquired.

"The same that I have given to others before him."

"And that is—?"

"Simply, that I have promised my parents that I will neither engage myself to, or marry any one, until I am twenty-one. Thereupon, he most unjustifiably made use of your name."

"My name!"

"He said that he knew you were his rival, and that I had refused him on your account; he added that he would soon remove you from his path and then he would urge his suit again."

Jack Harkaway was astonished at this revelation.

"He may have remarked that I admired you, Miss Van Hoosen," he exclaimed. "But he was quite unwarranted in saying what he did. If he attempts to pick a quarrel with me, let him beware."

"That is precisely what I want you to avoid," she replied.

"No matter; the days of dueling are not yet over. In France a man can seek satisfaction for his wounded honor."

"Let me beg and pray of you, to keep away from Lord Maltravers."

"I can make no promise."

"Remember that people tell strange tales of him. He has resided much in Italy and I have heard that he keeps a Neapolitan assassin in his pay."

Jack laughed heartily at this.

"I am not a child to be scared by such stories as that," he answered. "But if it will relieve your mind, I will undertake to be on my guard."

This was all Miss Van Hoosen could obtain from him, and she was very uneasy in her mind, when he rose to take his leave. He was much gratified with the result of his visit. For Lord Maltravers he did not care a snap of the fingers; but he was delighted to think that Lena Van Hoosen thought enough of him to send for and warn him of a danger which she fancied he was menaced with.

When he left the house, he walked slowly toward the club, where he knew he would meet some of his friends.

In the reading-room he encountered Dick Harvey, who had been his schoolmate and had accompanied him in most of his wanderings by sea and land.

In an arm-chair sat Professor Isaac Mole, his old tutor, who was fast asleep.

"How do, Jack?" exclaimed Harvey. "You see the professor is a little under the weather. Will you come to the committee-room? The meeting is convened for two o'clock and it is nearly that now."

"With pleasure," replied Jack.

Why the Travelers' Club was called by that name, no one had ever been able to discover. Its members were men who knew nothing of other countries, except what they read in books.

The special meeting, on the present occasion, had been called by Mr. Oldfoguey, the President, to discuss the actual habitat of that noble beast, the buffalo.

When Jack and Harvey entered the committee-room, there were about a dozen members present.

Mr. Oldfoguey called the meeting to order.

He was an elderly gentleman with a large bald head; he wore spectacles and a bottle-green coat with brass buttons.

"Gentlemen," he exclaimed, "you are assembled here to-day, for the purpose of discussing the actual location of the buffalo. I am of opinion that this gigantic beast is to be found in certain parts of Central Park, in New York city, and I am told that it roams at will over the plains of Jersey. It will be a valuable contribution to science, if we can settle this vexed question, and I invite the views of members on the subject."

Captain Cannon, a stout, plethoric gentleman, of a soldierly bearing, who had seen service in the Rifle Brigade, and was noted among his friends for being able to tell more wildly improbable yarns than any one else, responded to the call.

"The buffalo is a great fact," he exclaimed. "When in Canada West with my regiment, I got lost in the Hudson's Bay territory, and subsisted for six months on buffalo-meat. As far as I know, the buffalo is only found east of the Missouri river, and is rapidly dying out. Buffaloes are, to my certain knowledge, sir, used in New York for drawing street cars. It is naturally a beast of burden and very tame. When in Montreal, I used to drive a buffalo to a sleigh; he went well and was docile. The buffalo's favorite food is peanuts; he will also thrive on pop-corn."

The gallant captain sat down, after delivering this remarkable contribution to natural history, and Mr. Zebadiah Twinkle rose to his feet.

"Sir," he exclaimed, looking fiercely at the President, "I rise to a point of order. There are only twelve members present, and according to by-law 27 it requires fifteen to make a quorum."

Mr. Twinkle was tall and angular, and he glared defiantly around him.

The character of Mr. Twinkle was a very remarkable one. He was a gentleman of independent means, who had retired rich from the grocery business. His ambition was to be considered a sporting character. He was a great boaster, but when put to the test, generally collapsed in a ludicrous manner. In fact he was in common parlance a fraud and a blower, but he caused great amusement to his friends.

The entrance at this moment of five additional members of the club, effectually disposed of Mr. Twinkle's point of order.

"Good!" he said. "Now that everything is regular, I will proceed with my remarks. As my worthy and gallant friend Captain Cannon has stated, it is a fact that buffaloes exist in the city of New York, for whenever the citizens of that vast commercial metropolis go sleigh-riding, they invariably take their buffaloes. The animal is by no means ferocious, and is frequently taught by the Indians of Manhattan Island to follow them about like a dog."

Mr. Twinkle was followed by Jack, who could not help smiling at the dense ignorance displayed by the previous speakers.

"Mr. President and gentlemen of the Travelers' Club," he exclaimed, "allow me to state that the buffalo is a wild animal, which is only to be found on the plains of the Far West, where it ranges in herds in a savage state. It may be found as far south-west as Texas, and as far north as Montana."

"Is my veracity called in question?" cried Captain Cannon.

"Am I an ignoramus?" asked Mr. Twinkle.

"Order, gentlemen!" said the President, rapping the table.

"Allow me to make a suggestion," exclaimed Harvey. "As there is such a diversity of opinion about the buffalo, and the members of the club seem to be very hazy about the land in which he lives, I propose that a committee of—say five—be appointed to go to America and make a report."

This proposition was received with favor.

"Make it a substantive motion," said the President, "and I will take the sense of the meeting on it."

This was done, and the motion being put to the vote, it was carried, nem. con.

"Gentlemen," exclaimed Mr. Oldfoguey, "the power of appointment belongs, I believe, to me."

"It does, by virtue of the office you hold," replied Mr. Twinkle.

"Then I appoint as members of this investigating committee, Mr. Harkaway, Professor Mole, Captain Cannon, and Mr. Twinkle, with Mr. Harvey as Secretary, each gentleman paying his own expenses. The committee will start within a month for New York and report to us once a week."

"On the subject of the buffalo?" asked Captain Cannon.

"Precisely."

No objection was made to this, and those named on the committee accepted the honor imposed upon them.

Jack was willing enough to go to America, because Miss Van Hoosen was also going to that country, and he thought sufficiently well of her to wish to enjoy her society.

When all was settled, the meeting adjourned, and Jack went to apprise Mr. Mole of his selection as one of the Buffalo Investigating Committee.

The professor was still sleeping calmly, but he had attracted the attention of Lord Maltravers.

This scion of the aristocracy was about twenty-five years of age, very rich and extremely haughty.

His father died when he was young. He was educated by a private tutor who let him have his way in everything. His mother doted on and spoilt him.

Young, rich, titled, handsome, what wonder was it, that he was arrogant and thought himself cast in a superior mold to his fellow-creatures, whom he despised and looked down upon. Maltravers hated Jack Harkaway, in the first place because Jack paid him no deference, and secondly because he fancied Lena Van Hoosen preferred the dashing Jack to himself.

Knowing that Professor Mole was a friend of Jack's he lost no opportunity of insulting him.

Seeing him asleep, he twisted a piece of paper into what boys call a 'jigger,' and lighting it at both ends, placed it on the old man's nose.

He was accompanied by a young man who was his toady; his name was Simpkins, and in consideration of many favors bestowed upon him by Lord Maltravers, Simpkins was his most devoted servant.

"Ha! ha!" laughed Simpkins, "what an excellent joke; that will wake the old boy up."

"He's no right to sleep in a club, by Jove," remarked his lordship.

"Certainly not; it is not the proper place."

Presently the flame began to burn the skin of the professor's nasal organ, and he awoke with a cry of affright.

His hands instinctively sought his nose and he pulled off the 'jigger.'

"Confound it," he exclaimed, "my face is burnt. Who has done this?"

The two young men began to laugh loudly and were evidently enjoying their practical joke.

"I did it," said Lord Maltravers. "Is there anything else you want to know?"

Mr. Mole regarded him with indignation.

"If I wasn't an old man, I would chastise you for your insolence," he cried.

"Don't fall back on your age," replied Maltravers. "I am here to take the consequences of anything I may have done."

A quick step caused him to turn round.

"Are you?" asked a voice.

It was Harkaway, who, standing in the doorway, had been a silent spectator of the scene.

Lord Maltravers folded his arms.

"I am ready to answer you, or any one else," he said.

The two men regarded one another sternly.

"THE DUEL ON THE SANDS."

Jack Harkaway was afraid of no man living, and though averse to quarreling, he always supported his friends.

"You have committed a gross outrage on Mr. Mole!" he exclaimed; "and in his name, I demand an apology."

"Indeed!" sneered Maltravers.

"And what is more, I mean to have it."

"Is that so?"

"Apologize, my lord, or something may—nay, will assuredly happen which both of us will have cause to regret."

"You want, sir, what I do not feel inclined to give you," replied Maltravers. "I am not in the habit of apologizing to a gentleman, and should not think of doing so to you."

"That is as much as to say that I am not a gentleman," exclaimed Jack, the hot blood rushing in a crimson tide to his face.

"You are perfectly at liberty to place whatever construction you like on my words, sir."

Simpkins smiled approval in his usual insipid manner.

"Bravo!" he lisped. "Very fine, indeed."

"I ask you once more," said Jack, "if you will make the amende honorable to my friend?"

"And I distinctly refuse to do so."

"In that case I shall chastise you, as I would any yelping cur which annoyed me in the street. Mind yourself, my lord," Jack exclaimed.

He raised his fist and dealt Maltravers a blow which the other vainly endeavored to ward off.

His lordship fell heavily against the wall and the blood flowed from a cut in his face, which extended the whole length of the right cheek.

"Good heavens!" said Simpkins. "The man is a butcher. He has marked you for life, Maltravers."

The latter applied a silk handkerchief to his hurt, withdrawing it covered with the hot blood.

"Coward!" he exclaimed. "You struck me with a ring on your finger."

"Served you right," said Mr. Mole. "I wish he had given you more of it. This will teach you not to insult an old man, who never did you any harm."

"I am not talking to you, imbecile," hissed Maltravers.

He turned to his toady:

"Give me your arm, Simpkins," he added.

"With all the pleasure in life," was the reply.

"You shall hear from me, Mr. Harkaway," continued Maltravers.

"Whenever you please," answered Jack, carelessly.

"I presume you will not refuse me the satisfaction of a gentleman."

"You can rely upon me."

His lordship bowed stiffly, and, still holding the handkerchief to the cut, from which the blood trickled slowly, left the room.

"Am I much hurt, Simpkins?" he asked.

"Cut all to pieces."

"Shall I be disfigured?"

"You will always have a scar, I fear," replied Simpkins.

"Curse that fellow!" cried Maltravers, between his clenched teeth, "he shall pay a terrible reckoning for this."

"Why didn't you hit him back again?"

"He took me by surprise, and he hit with such force, that he knocked me out of time. My head swims now and I am so dizzy, I feel as if I should faint."

They passed out of the door, leaving Jack and the professor together.

The latter shook Harkaway by the hand very warmly.

"Many thanks, my dear fellow," he exclaimed. "You acted very properly in punishing that man. He has made a dead-set at me for some time past."

"On my account; I know it all," replied Jack. "This row was bound to come. I was warned of it only this morning."

"Do you think he means to fight?"

"I am sure of it."

"And you will meet him?"

"I do not see how I can avoid it. No matter; vive la bagatelle, as the French say. A life of adventure for me."

Jack related to Mr. Mole the proceedings of the club and the selection of a committee to proceed to New York. In a short time Harvey came in, and when told about the quarrel with Lord Maltravers, gladly consented to act as his second, if a challenge should be sent.

The law of England forbade dueling, but in France, hostile meetings frequently took place, and they did not doubt that the encounter would be arranged for that country.

As the challenged party, Jack had the choice of weapons and resolved to choose swords, as he was an expert swordsman.

He invited the professor and Harvey to dine with him at his hotel, intending to go to the theater afterward, but this intention was frustrated by the visit of Captain Cannon, who sent up his card saying he wanted to see him on urgent business.

Jack stepped into an inner room and at once accorded him an interview.

"Very sorry to trouble you about an unpleasant matter," said the captain. "But Lord Maltravers has asked me to act as his friend."

"I understand," replied Jack. "You have heard all about this unfortunate business."

"Surely, and if a blow had not been struck we could have arranged it. As it is, a meeting must take place."

"Where?"

"At Calais, by daybreak to-morrow morning."

"So soon?"

"Yes, it is useless to delay," replied the captain. "The express train leaves at half-past eight. Who is your second?"

"Mr. Harvey."

"Very well. I shall expect him at my hotel, the Imperial, after our arrival. We will arrange everything. It is all very simple. I fought a dozen duels before I was your age and always winged my man."

"Really!"

"Fact, I assure you. Keep your courage up."

"No fear of that," replied Jack. "I hope your principal will be as calm as I am."

"Oh! he won't show the white feather," answered Captain Cannon. "The Maltravers blood may be bad, but there isn't an ounce of cowardice in it. Good-by, we meet to-morrow."

Jack nodded, and seeing Captain Cannon out, excused himself to Mr. Mole and sent for Monday, to whom he confided the fact that he was going to France to fight a duel.

"You fight a jewell, Marse Jack?" said Monday; "what you want to do that for?"

"It is a point of honor. Don't you see? I struck this man and must give him satisfaction."

"You leave him to me and I put six inches of bowie-knife in him, for suah."

Monday's eyes gleamed like those of a cougar, and it was clear that he meant what he said.

"Don't ever talk to me like that again," exclaimed Jack. "I am no assassin."

By half-past eight, Jack and Harvey were comfortably seated in a carriage of the mail train on their way to France.

"If I fall," said Jack, "I want you to see Miss Van Hoosen and tell her that my last thoughts were of her."

"I'll do it," replied Harvey. "But I do not think anything will happen to you."

They arrived in due course and Jack retired to rest, while Harvey sought Captain Cannon to arrange the preliminaries.

He found the captain drinking wine with Lord Maltravers and talking loudly about the exploits of his youth.

"Ah! Harvey," he exclaimed, "here you are. Sit down and join us in the foaming goblet. That's a good phrase I flatter myself. A duel stirs my blood and carries me back a long way. I recollect when I was quartered in Dublin, a fiery young Hussar took exception to something I said and threw a glass of wine in my face—he did, by Jove, sir. That was a case of pistols for two and a coffin for one. I met him in Phœnix Park the next day and at the first fire, I shot him through the heart, and went to the expense of having his body embalmed to send home to his mother."

"Very considerate of you, I am sure," remarked Harvey.

"Oh! it's just like me. I'm all heart. By the way, what weapons does your principal select?"

"Swords."

"Humph! I'd rather it had been pistols, because the affair would have been over sooner; but no matter. I have an elegant pair of rapiers. We will meet you at six o'clock on the sands at low-water, one mile south of the town."

"That is sufficient," answered Harvey.

He refused to spend the night in a spree as the captain evidently intended to, and returned to his own hotel.

At five o'clock he had Jack up, and they sought the appointed spot, finding Lord Maltravers and his second already there.

In an instant the principals stripped to their shirts and grasped the weapons which were handed them.

The swords were of highly tempered steel, sharply pointed and as pliable as a willow wand.

The sun was just rising in the east, gilding the horizon with its burning rays. A few fishing-smacks lay in the offing. The tide was on the turn, and the wavelets plashed mournfully on the sand, as if singing a requiem.

"En garde!" cried Maltravers.

Jack placed himself in position. His right arm and knee advanced, and his left hand by his side.

The swords clashed as they crossed each other, and recovering, the duelists watched carefully for an opening.

Lord Maltravers lunged in carte, but his thrust was delicately foiled by his opponent, who parried it skillfully.

A long strip of plaster hid the cut on his lordship's face, which was ghastly white and terribly in earnest.

For some minutes they fenced with the adroitness of veteran swordsmen, neither gaining the slightest advantage, though a hectic spot which appeared on Maltravers's face, indicated that his mind was less at ease than Jack's.

Suddenly Jack ceased to act on the defensive and became the aggressor, breaking down his lordship's guard and pinking him slightly in the left arm.

"First blood!" said Harvey; "are you satisfied?"

"Confound it, no. This is a duel to the death," replied Maltravers, his face distorted with passion.

"As you please," replied Jack.

Again, they faced one another, the wounded man having hastily tied a piece of his shirt sleeve round his arm.

The swords clashed in the bright morning sunshine, which every moment became brighter.

In vain Maltravers strove to injure his enemy. Each thrust was parried and he panted with exertion, while tears of impotent rage started to his eyes.

"Ha! I have you now," he exclaimed, as the point of his rapier touched Jack's breast.

"Not quite," replied Jack, who threw himself back, instantly recovered, and lunging in tierce, sent his weapon through the left shoulder of the nobleman.

Maltravers staggered; he leant upon his sword, which snapped in half, and he sunk upon his knees, his face convulsed with pain.

"That ends it," exclaimed the captain. "I confess myself satisfied."

"No! No!" cried his lordship, seizing the pointed end of his rapier and binding a kerchief round the broken part so as to hold it more securely.

"Surely, you will fight no more?"

"I will fight till I drop."

Harkaway broke his sword in half over his knee and grasped the narrow end, in the same manner as his adversary.

"I am willing," he replied.

"My dear fellow," remonstrated Harvey, "are you insane?"

"By no means," was the calm and confident reply. "I did not come here to play, and besides, I hate to leave my work half finished."

"Eh! the wretch," said Maltravers, bursting with rage, "he mocks me; but we shall see."

Jack sunk on his knees in front of Maltravers, and they were now so near, that their eyes returned flash for flash and their hot breath fanned each other's face.

Maltravers was bleeding profusely, his blood dropping on the thirsty sand, which greedily sucked up the ruby fluid, and the ghastly pallor of his face deepened.

In a few minutes he had succeeded in inflicting a few scratches upon his adversary and he grated his teeth with grim satisfaction.

This irritated Jack, who precipitated matters, by receiving the point of his lordship's weapon in his left arm and throwing himself upon him, piercing his breast and bearing him to the ground.

Now Maltravers could utter no protest, for he fainted and extended himself on the ground in the attitude of a corpse.

Jack hurriedly put on his coat.

He was bleeding, but in the excitement of the moment felt no inconvenience, and it was not till his wound stiffened that he knew he was hurt. They began to leave the spot.

"Look here," said the captain, "this is contrary to all precedent. I recollect when I fought the major of the Twenty-seventh, and left him for dead, we sent a coach after him and a doctor."

"All right," responded Harvey, "we will do that for you."

He departed hastily with Harkaway, and the captain dragged the insensible body of Maltravers to a spot further inland, where the rapidly advancing waves could not touch it.

For the next hour he busied himself in stanching the blood, which indeed was the only way of saving the defeated man's life. At the expiration of that time he perceived a carriage driving furiously along the sand.

When it reached the spot where the captain was standing a gentleman stepped out.

"I am the doctor," he said.

Captain Cannon nodded, and after a brief examination the medical man ordered Maltravers to be driven to the hotel.

For some hours he hovered between life and death.

The captain remained in constant attendance by the bedside, until a severe attack of fever supervened, when a professional nurse was hired.

On the third day the crisis came.

It was midnight when the doctor left the sick man's room and sought the captain.

"Has this gentleman any friends?" he inquired.

"Yes, in England," was the reply.

"It will be best to send for them without delay."

"Is the case so grave as that?"

"I cannot answer for the result," replied the doctor.

Captain Cannon at once telegraphed to Lady Maltravers, the mother of the sick man.

That night the patient was very feverish and restless; he recognized no one.

In the afternoon of the following day Lady Maltravers arrived at the hotel accompanied by Bambino, his lordship's Italian servant.

This fellow had a most villainous countenance and it was said that he had been condemned to the galleys for a term of years, in expiation of some terrible crime.

"My son! Where is my son?" demanded Lady Maltravers.

She was conducted to his room and from that time forth watched over him with all a mother's devotion.

THE ASSASSIN AT WORK.

Thanks to his youth, aided, by a strong and vigorous constitution, Lord Maltravers passed through the valley of the shadow of death without succumbing to the fell destroyer.

In a fortnight he was out of danger.

The doctor predicted that his recovery would be slow, and advised that he should remain where he was until his strength was fully established.

Lady Maltravers returned to London, rejoicing that her child was saved to her, for with all his faults she loved him with the strong intensity of a fond and over-indulgent mother.

Consequently his lordship remained at Calais in the charge of his faithful valet, Bambino.

One day, while sitting up for the first time, his pale and haggard face brought into prominence by the rays of the sun which streamed in through the open window, he received a letter from Simpkins, to whom he had written for news.

In this letter he was informed that Harkaway and four friends were about to depart for New York in a few days on board the steamer Erin, Miss Van Hoosen having preceded them by a week.

"Bambino," exclaimed his lordship.

"Signor," replied the valet, who glided softly to his side, with the noiseless motion of a black snake.

"Three years ago, when I was in Florence, a man named Bambino was being tried for the commission of a double murder. He had killed the woman he was about to marry and a man of whom he was jealous. The trial excited great interest; and finally, being found guilty, Bambino was condemned to the galleys for the term of his natural life."

The Italian raised his hand deprecatingly.

"That was in the past, master," he said.

"True; but it is necessary that I should recall it. I took an interest in you, visiting you in prison before your transportation to the coast to begin your life-long slavery. I wanted just such a man as yourself."

"You have ever found me grateful, signor."

"Don't interrupt me. You swore by your faith that if I procured your release, your life should be mine to dispose of, as I thought fit. By expending large sums in bribing your jailers, I contrived that you should escape, and since then you have lived a life of comparative ease and luxury."

"It is true," exclaimed Bambino.

"The time has how arrived when I want you to exercise your peculiar talents on my behalf."

"You have but to command, my lord," replied the Italian. "It is for me to obey."

"Good. You have seen Mr. Harkaway?"

"I know him well."

"Again, good," exclaimed Maltravers, whose dark eyes flashed vindictively. "Harkaway is my enemy!"

"He shall die," said Bambino, solemnly.

"Very well. It is for you to see to that. I am in the position you see me now, through that man. He starts for New York on Saturday in the steamer Erin, following a lady I love, whom he intends to steal from me and marry, if I do not stop him. You will embark on the same vessel, and by the time I am well enough to join you in New York, you will have rendered a good account of him."

"His spirit shall have gone to the land of shades. I, Bambino, swear it," said the Italian.

"I rely on you. Is it requisite for me to say anything more?"

"Nothing, my lord."

"Then take what money you want and be off," returned Lord Maltravers.

That night Bambino was on his way to Liverpool, from which port the steamer started.

ADÉLE.

Lord Maltravers was reading a book when the door opened and a beautiful girl with long silky dark hair entered the room.

Her face was sad, and there were traces of tears on her pale cheeks.

Springing forward, she threw herself on her knees before him, and seizing his hand, which she covered with kisses, exclaimed, in pathetic tones, "Oh! Arthur, at last I have found you."

"Adéle!" he said, while a hectic flush mantled his cheek.

"Yes," she replied. "It is your own Adéle, the little girl you vowed to love; Adéle whom you married two years ago in the little French village in the Pas de Calais. Oh, Arthur! how could you desert me?"

"I—I never married you," he answered, stammering a little.

"Indeed you did."

"It was a mock marriage."

"The good curé who united us is alive. He will bear evidence that I am your wife. I, Adéle Bellefontaine, am in reality Lady Maltravers."

"It is false."

"Oh! do not repudiate me, for, darling, I love you," she pleaded. "If you have forgotten me, I can never forget you."

"How did you find me out?"

"I read an account of your duel in the papers; they said you were ill and suffering; I walked fifty miles to come and nurse you, because I was too poor to ride."

"You shall have money to go home again, foolish girl," said Maltravers.

"I do not want it. All I ask is your love," replied Adéle. "Let me have the sweet privilege of waiting upon you, Arthur. I will be your servant, your slave. Do not, for heaven's sake, drive me from you."

Maltravers was ill at ease and could not disguise his agitation.

Two years before, as the poor girl had truly said, he had met her in a secluded village, where he was fishing. He had married the poor peasant girl and then basely deserted her.

Some letters he left behind revealed his true name, and at the first chance Adéle had come to him, to beg once more for that love for which she was pining.

It was impossible for him to acknowledge her claim or recognize her before his friends, and for a moment he did not know what to do.

His mind, however, was soon made up; he would threaten her, deny her story, and drive her from him.

"Rise," he exclaimed; "you are an impudent impostor. If you do not instantly quit this room I will have you arrested. It is the correctional tribunal which should deal with such creatures as you."

Adéle rose to her feet and clasped her head with her hands as if her throbbing brain would burst.

Could she believe the evidence of her senses?

"My God!" she cried. "He sends me away! Does he not know that I have a heart which will break? Are a man's vows traced upon the sand or written in water when he tells a woman he loves her?"

"Go," continued Maltravers, sternly.

For a minute she was completely overwhelmed and stood like one in a dream.

"Yes, I will go," she said in a choked voice. "Heaven knows whither! The folks in my village shall never see me again, or know my shame. I said I would go after my husband and bring him back. My father and mother were to prepare a fête. That is over. I have been gathering Dead Sea fruit. It has turned to dust in my hand. I trusted a bad man and my punishment is more than I can bear. Yet, the water is near, and there is one refuge for the weary and heart-broken. Farewell, Arthur. May God forgive you, as does your Adéle."

Not a muscle of Maltravers's face moved. He stared coldly at this poor girl whom he had wronged so infamously and there was an aristocratic sneer on his well-cut lip.

She staggered rather than walked to the door. She descended the stairs like one dazed. The iron had entered into her soul, and those hearts which have been seared by the burning hand of misfortune can alone sympathize with her.

Adéle gained the street. Mechanically she sought the harbor and entered upon the broad pathway of the long pier. There was a wild desperation in her eyes; her face was lighted up with a half-insane gleam; no tears came to her relief. At times a choking sob broke in her throat—this was the only evidence of feeling that she gave vent to.

A drizzling rain was falling which kept away the usual promenaders on the pier. The tide was flood and several vessels were sailing out of the harbor.

She paid no attention to anything, seeming to be absorbed in her misery. Her eyes became fixed and glassy. Occasionally she moaned as if in pain, and pressed her hand to her side to still the beating of her heart.

When the end of the pier was reached, she stopped, raised her eyes to heaven and her lips moved as if in silent prayer.

Then she sprung lightly over the parapet and fell into the foaming sea, whose waves were beating in clouds of spray against the wooden supports of the pier.

A large merchantman was passing out of the harbor at the time with all sails set, and the rash act of the poor suicide was witnessed by the sailors on the deck.

Without a moment's hesitation one gallant fellow jumped overboard and swam toward the drowning girl.

He succeeded in reaching her as she was about to sink, and held her up, until a boat from his ship came to her rescue.

Adéle and her brave preserver were picked up and conveyed to the vessel, she being in a dead faint.

"Holy Virgin!" exclaimed the sailor, as his eyes fell more closely upon the girl's features. "It is Adéle Bellefontaine, from my village of St. Ange, just as sure as my name is Jacques Belot and she was the only girl I ever loved, until she married that scoundrelly Englishman, who deserted her. If it had not been for Adéle, here, I should never have gone to sea."

"What are we to do with her?" asked the captain. "The wind and tide are against us and it is bad luck to put back."

"Take her with us, captain," said Jacques, who was a fine, handsome young sailor.

"It is bad luck to have a would-be suicide on board," remarked the boatswain.

"Ah! bah! you old croaker," replied Jacques. "How do you know the girl intended to kill herself?"

"I saw her deliberately jump into the sea."

"And I saw her blown over the side of the pier, by the wind."

The sailors laughed at this sally, which encouraged Jacques. "Won't you take her to New York, captain?" he continued.

"Yes," replied the captain, good-naturedly, "I suppose I may as well. She will be a companion to my wife. Carry her below, friend Jacques, but mind you don't get so dazzled by the girl's pretty eyes, as to neglect your duty. Take her away."

"Ay, ay, sir," answered Jacques, who raised Adéle's slender form in his arms and transported her to the captain's cabin.

The skipper's wife was glad of a companion and at once proceeded to restore her to consciousness, while Jacques related the affair.

When Adéle opened her eyes she looked wildly around her and murmured: "Is this death?"

"No, deary," replied the captain's wife, "this is life. You were saved by Jacques here."

"Oh! let me die."

"What for, child? You are young and pretty. Life should have its charms for you."

"I have seen him and he drove me from him. He says I have no claim on him and threatened me with the police. Oh! it has broken my heart."

She burst into a paroxysm of bitter tears, but they relieved the overcharged fountains of her soul.

"It will do her good," exclaimed her kind protectress.

Jacques Belot gnashed his teeth.

"She said 'he' and she has seen him," he[Pg 5] muttered. "I know what it means well enough. That vile Englishman has gone back on her. I have seen him, I can recall his face like a book. He is a lord, they say; his name is Maltravers. You see I forget nothing. We shall meet one day, and it seems to me that there will be a little account for me to square with Mr. Englishman—sacré-e-e!"

Presently Adéle recognized Jacques, and greeted him as an old friend, but not as a former lover.

To him and the captain's wife she related her story, gaining much sympathy from them.

"Forget this milor'," said the captain's wife.

"Impossible," rejoined Adéle.

"He is unworthy of you. Go to America and marry this brave fellow who loves you and has saved your life."

Adéle shook her head sadly.

"Madame," she replied, "though I am deserted, I cannot fail to recollect that I am the legal wife of Lord Maltravers."

"At least promise that you will not again attempt to commit suicide."

"I promise."

With that they were obliged to be content and so the good ship Notre Dame de Calais sailed along the English Channel and out into the storms of the broad Atlantic.

THE VOYAGE.

Some days afterward the ocean steamship Erin started from Liverpool, having on board, among others, Jack Harkaway and his friends, and Signor Bambino, an Italian gentleman, who stated that he was proceeding to New York on business of a commercial nature.

Jack and Harvey took no interest whatever in the absurd question about the buffalo, which agitated the quidnuncs of the Travelers' Club.

The reason Jack was going to New York was simple enough; he wanted to be where Miss Van Hoosen was; and Harvey went because his friend Jack did.

After the first sensations inseparable from a sea-voyage were overcome, the saloon passengers began to fraternize, and among the most popular in the smoking-room was Signor Bambino.

Four days after leaving Liverpool, the Erin encountered severe weather; the decks were swept by the sea fore and aft, and for six hours the hatches were battened down. When the storm ceased, the passengers came on deck once more and enjoyed the calm of the evening.

Jack and Bambino played eucher until midnight, when the Italian threw down the cards.

"I have had enough of it, if it is all the same to you," he exclaimed.

"But you have lost heavily," said Jack.

"Bah! what is that? to-day we lose, to-morrow we win. It is only a trifle, after all."

"As you please," replied Jack.

"Let us take a stroll on deck," continued the Italian.

"With all my heart."

They quitted the saloon and went on deck, which the quick eye of Bambino saw was deserted.

A thick mist had arisen, and though the captain was on the bridge his form could not be distinguished.

The phosphorescent pathway in the wake of the big ship gleamed and scintillated.

"How beautiful," remarked Jack.

"Yes," replied Bambino. "It looks like a sea of fire. One might walk on it."

"I should not like to try," Jack said, laughing.

"Suppose you do make the effort."

At these words of Bambino, Jack turned half round sharply, and faced him squarely.

"What do you mean?" he demanded.

"Precisely what I say," rejoined Bambino.

They were standing at the stern of the ship, right behind the wheel-house.

"Who are you, and what do you want of me?" inquired Jack, who became suspicious.

"I have a fancy to throw you into the sea."

"Madman!"

"Yes, if you like. I am peculiar at times. Come! how do you like the look of this?"

As he spoke, Bambino drew a long knife and made a thrust with it at Harkaway.

The latter stepped back quickly, receiving the point of the knife in the fleshy part of his right arm.

It was merely a graze and did not cause him any serious inconvenience, but it served to put him on his guard.

Being unarmed himself, he concluded that his best course would be to grapple with his assailant, which he accordingly did, dashing the knife from his grasp by a lucky hit and placing himself more on an equality with the cowardly assassin.

The struggle that ensued was short, sharp and decisive, for the superior strength of the robust Englishman soon told on the effeminate Italian, who, deprived of his knife, was not very dangerous.

Jack threw him on the deck and pinned him by the throat.

"Villain," he cried, "what was your object in attacking me?"

Bambino made no answer.

"Tell me," continued Jack, "or I'll strangle the life out of you!"

He compressed his fingers mere tightly and the assassin's eyes started from their sockets, while his face assumed a purple hue.

"Speak, speak!" persisted Jack.

A gurgling sound came from the man's mouth, and he made signs that he was being stifled.

When the gripe was slightly relaxed he said: "I am a poor adventurer, and fancied I could get money by robbing you."

"That is not the truth; robbery was not your object, but murder."

"Well, I will confess," exclaimed Bambino, who was afraid of being killed and thought he could serve his employer better alive than dead.

"Make haste."

"Lord Maltravers ordered me to kill you. I am simply a hired assassin. Let me live."

All was instantly clear to Jack.

"I am satisfied," he replied.

"You will let me go, now?"

"Indeed, I will do nothing of the kind. I must make you a prisoner for my own protection, and when we reach New York the authorities will decide what is to be done with you."

It was in vain for Bambino to protest; he submitted to his fate in sullen silence, allowing himself to be dragged amidship, when Jack explained to the first officer what had happened.

The watch was called, and the would-be murderer, gnashing his teeth at the failure of his attempt, was taken below and confined.

The next morning Jack appeared at breakfast in the saloon as if nothing had happened, but he told Mr. Mole and Harvey that an emissary of Lord Maltravers had attempted his life.

"This is very important," observed the professor. "It shows to what lengths Maltravers will go to remove you from his path. Let the man's full confession be taken; he can then be used as a means for the arrest of his lordship, who, if I am right in my law, can be sent to prison, as the fellow's accomplice."

"Certainly, he can," replied Harvey.

"It is not very pleasant," remarked Jack, "to know that an enemy is plotting against you in a far-off country and sending out men to kill you."

"I have an idea," said Mole.

"Something novel for you, sir."

"Oh! no. This old head has been prolific in its time. Let us form ourselves into the Jack Harkaway guard."

"Splendid idea," cried Harvey. "I volunteer for the service. You and I will arm ourselves and one or both of us will be with him, night and day."

"No, no," said Jack, much touched at this proof of the devotion or his friends, "it is unnecessary."

"On the contrary," answered Mole, "I am sure that this attempt will be followed by others."

"Well! If you insist upon it—"

"We do," said both the professor and Harvey in chorus.

Jack shook their hands in token of gratitude, and as Mr. Mole had brought out a small arsenal of pistols and knives in his trunk, for use in an emergency, he promptly armed both himself and Harvey.

Meanwhile Jack remained on deck.

Suddenly the man on the look-out reported a sail to leeward.

The steamer altered her course and made directly for the vessel, as she showed signals of distress and appeared to be in a water-logged condition.

When near enough the captain ordered the engines to be stopped and a boat lowered.

This was done and a crew manned the boat to row to the distressed craft.

An event like this relieved the monotony of a sea voyage and the deck was soon crowded with passengers.

In half an hour the crew had rowed to the vessel and returned without boarding her.

They reported that the ship was leaking badly and had been abandoned by her crew, after suffering severely from the late storm.

Her masts had all gone by the side; her sails were blown to rags; her bulwarks were stove in. She was rudderless and it was a wonder how she kept afloat.

When this was reported and the boat hauled up to the davits once more, the captain of the steamer ordered the engineer to go ahead, and proceeded on his course.

He felt that he had done all that humanity required of him.

Scarcely had the dull, heavy beat of the enormous engines made themselves heard in the vibrating ship than a commotion was seen in the forecastle.

Jack ran forward to ascertain the cause.

A man was seen struggling fiercely with the sailors, who were trying to detain him.

It was Bambino.

By some means, while the steamer was lying to, he had contrived to escape from the place in which he was confined.

"Stop him!" cried Jack. "Knock him down, he is dangerous."

Bambino, however, was too much for his opponents, and dashing them on one side, made a flying leap and sprung over the side into the sea.

Whether he dived like a duck or was sucked under the ship and struck by one of the flanges of the screw, it was difficult to tell.

He was looked for in all directions. The steamer was again stopped and the boat lowered, but nothing could be seen of the man overboard.

"He is gone to his last account," said the captain, "and he is no loss."

"I'd rather have had him live," replied Jack, to whom this remark was addressed, "and somehow, I can't quite make up my mind that the fellow was born to be drowned."

"Hanging is certainly more in his line."

"That is so," said Jack.

The steamer once more proceeded on her way, and Jack amused himself by scanning the expanse of ocean, through an opera-glass.

He fancied he saw a dark object resembling a man struggling with the waves in the vicinity of the abandoned vessel.

It was quickly left behind, and thinking it might have been his imagination, he dismissed Bambino from his mind.

THE ABANDONED SHIP.

The crafty Italian, however; was not so easily disposed of.

He was perfectly at home in the water, and had, by diving, kept himself concealed from view, his intention being to swim toward the abandoned vessel, which he had seen as soon as he came on deck.

He knew that a long term of imprisonment awaited him, if he was taken to New York, and he deemed any risk, no matter how desperate, preferable to that fate.

This decided him in jumping overboard.

In time, he succeeded in reaching the water-logged ship, which rolled uneasily upon the heaving bosom of the deep.

Climbing up the chains, he got on board and found himself the sole master of a fine vessel.

She was partly laden with timber, which accounted for her keeping afloat, in the disabled condition in which she was.

His first task was to examine her cabins, which were free from water.

In the forecastle he found everything in disorder, as if the vessel had been abandoned in a hurry and without sufficient cause.

Probably the ship was overwhelmed by the fury of the storm in the dead of night, and the crew, seized with a panic, had lowered the boats.

Her figure-head had been washed away and the name on her stern was not decipherable.

Bambino could only make out the letters, "v—r—e—a—n—d—ris."

Going aft, he descended the companion-ladder, and entered the captain's cabin, where the same indications of haste were noticeable as in the forecastle.

Everything had been thrown about in reckless confusion, and many articles of value were piled up, as if to be carried away.

In various lockers he found provisions in plenty, unharmed by the saltwater. Cans of meats, sardines, biscuits and fruits, as well as bottles of wine, brandy and beer.

His spirits rose at this timely discovery, and his elation increased as he reflected that the ship would keep afloat for some time, unless engulfed[Pg 6] by another storm, of which there was no indication at present.

Sitting down, he placed on the table of the cabin an excellent repast, of which he partook with a good appetite, washing it down with copious draughts of wine.

His satisfaction culminated when he found a box of fine cigars, which he promptly began to smoke, a box of matches affording him all the light he wanted.

While he was congratulating himself upon his good luck, he heard a peculiar sound.

This came from what appeared to be an inner cabin, the door of which was locked.

The sound resembled the moaning of some human being in deep anguish.

Somewhat superstitious, Bambino crossed himself and muttered a prayer.

Again the sound was repeated.

Bambino's hair began to erect itself, and he advanced to the partition, inclining his head in a listening position.

THE MYSTERY OF THE DESERTED VESSEL.

After listening at the partition for some time Bambino became convinced that a human being was confined in an inner cabin.

Frequently he heard sobs and groans mingled with exclamations in the French language, with which he was well acquainted.

A further examination showed him a door, against which several pieces of furniture were jammed, they having evidently been thrown against it during the progress of the storm.

This had effectually prevented the egress of the unfortunate person inside.

Being a powerful man, the Italian exerted himself to the utmost and succeeded in removing a bureau, some chairs and a heavy table which were piled up in confusion.

Then the door flew open, and he beheld a lady lying on a bed, and it was easily observable that she was in a state of complete exhaustion, having been many days without food.

Had not help come when it did, she could not have survived much longer.

Though the face was very beautiful, the cheeks were sunken, emaciated and hollow; her long silken hair hung in disheveled masses over her shoulders, and in her deeply expressive eyes there was the glare of incipient insanity.

No sooner did the girl see Bambino than she endeavored to rise, but was compelled to fall back again by weakness.

"Who are you?" he asked, tenderly.

"I am an angel now," she replied. "Death has held me in his arms. I do not suffer any more, though it was hard and bitter to die."

Her voice was faint and feeble. There was that in her words and manner which indicated that her mind was wandering. Reason had tottered on its throne, until it had finally given way beneath the weight of her sufferings.

Seeing that she was in want of nourishment, he procured some food which he administered with a spoon, afterward compelling her to drink some wine.

Toward night she improved considerably, and fell into a refreshing sleep.

Bambino went repeatedly on deck to look out for a sail, but did not see one.

His position was a precarious one, for should another storm arise, there was little doubt the vessel would either capsize or break her back.

He drew some consolation from the fact that he was in the path of the steamships which were constantly crossing and recrossing the Atlantic ocean.

Two days passed, during which the lady remained in a comatose state; but, as he continued to feed her at intervals, she gradually regained her strength, and on the third day was able to get up and converse.

Her mind, however, was gone. She talked incoherently, persisting that she had died during the storm, and that she was a spirit.

"When I was alive," she would say, "I lived in France and I married an English nobleman. When he dies and comes to the land of spirits, he will not deny that I am his wife, though on earth, he drove me from him and broke my heart."

"What was his name?" asked Bambino, who became interested in her random utterings, he scarcely knew why.

"Lord Maltravers; you see I remember that, though I cannot recollect all things that happened before I died. I was called Adéle."

Bambino started and visibly changed color.

He had heard his master speak of this girl, and it appeared to him that he had made an important discovery.

Maltravers had admitted to this confidential villain that he had legally married the girl, and he hoped that she was dead, as she might give him some trouble if she lived.

Slave as he was, bound hand and foot to his titled master, Bambino felt that, with this girl in his possession, he would have a powerful weapon to use, should he ever come into open conflict with him.

He determined to say that she was his sister and that the captain and crew of the ship had left them behind in their hurry to quit, while he could easily add that Adéle had become crazed with terror.

A week went by; and though Adéle grew stronger, there was no amelioration in her mental condition.

She was quiet and even childish. Never did she utter any threats against Lord Maltravers. She loved him in a sweet, innocent way that was very affecting.

In a locket, which she wore around her neck, she had a faded photograph of the handsome, bad man, who had made her the plaything of an idle hour and ruined her young life. This she would take from her bosom where she concealed it and kiss with the greatest rapture, pressing her lips to it and murmuring words of purest affection and despairing love.

It was a sight to make the hardest heart feel, and bring tears to the eyes of the most callous man of the world.

Even Bambino, wretch that he was, had known what it was to love, and he sighed for her misery.

At length the wished-for sail hove in sight, and the Italian contrived to attract the attention of the crew, who lowered a boat to come to their rescue.

He went below and roused Adéle, who was bending over the photograph of the loved one, very much as a little child plays with a pretty toy.

"Come, mio caro," he exclaimed, "we are going on board another ship, which will take us to a great city. Put that thing away."

Adéle held up the picture, while a smile overspread her countenance.

"Isn't he lovely?" she asked.

Bambino set his lips firmly together, while the dark eyes—peculiar to the Latin race—flashed forth their fire.

"I can't say anything against him," he replied, "for I owe him much; but, cospetto! you and he will go to different places when you die."

"I am dead. You know that," said the simple-minded girl. "But will he not come to me in time and ask my pardon? Will he not fold me in his arms as of old and call me his darling?"

"Possibly."

"Oh, yes," said she, as her eyes rolled in an ecstasy of unbounded affection. "It must be so. There must be some recompense for the pure in heart, hereafter."

Bambino was touched.

He patted her beautiful hair with the air of an affectionate brother.

"Would to God, my child," he said, "that I had won your love instead of the woman's who—but no matter; my hand is red with her blood."

Adéle looked at him in dread surprise.

"Did you kill her?" she asked.

Bambino laughed, in a harsh, metallic tone.

"She is dead," he replied. "Ay, and—Corpo di Baccho! the man is in the grave, too."

"Man! what man?" inquired Adéle.

"Ask me no more questions, unless you want to madden me," cried Bambino. "I thought the wound was cicatrized, but you, with your childish questions, set my blood on fire. I loved that woman."

"Maltravers loved me once, yet I did not kill him when he deserted me and afterward drove me from him, when I laid my heart at his feet. How can you kill those you love?"

Bambino could say no more. He led Adéle gently but firmly up the companion-ladder, and in a few minutes the boat from the steamer was alongside.

They were taken off the ship. He told his story and excited much sympathy, especially when he reached the vessel, which was bound to New York.

Adéle and he were given berths in the intermediate part of the ship, which is amidships, and in five days they found themselves in New York.

Bambino was careful to conceal his right name, as he knew the log would be published in the papers, and might reach Harkaway's eye.

The Italian resolved to keep Adéle in his charge, as a counterfoil to any ill-treatment he might receive from Lord Maltravers.

When the steamer arrived, he went to a hotel and having secured attendance for Adéle, cast about for some place where he could place her.

In a paper he saw an advertisement to this effect:

"Astrology.—Madame Vesta Levine, the only real fortune-teller in the city—electric baths—galvanism. Boarders taken. W. 32d St."

The morning after his arrival he called upon Mme. Levine, who was a middle-aged lady, with an intellectual face.

She did not look like a charlatan, and exhibited a diploma from a medical college, which proved that she had some knowledge of the healing art.

He was received in her office, which contained only a few chairs, a table and some books on a shelf, having no skulls, stuffed snakes and the ordinary stock in trade of a fortune-teller.

"What can I do for you, sir?" she demanded.

"I have a sister," replied Bambino, "whose mind is affected through a disappointment in love and a subsequent shipwreck at sea. She is young. I do not wish to put her in an asylum. I have great faith in electricity and I will place her in your care, paying three months' board in advance, if you will receive her."

"I shall be glad to take her as a patient," answered Mme. Levine.

"You will try to cure her?"

"Undoubtedly."

"I must warn you that she imagines she is a departed spirit."

Mme. Levine smiled.

"That is nothing," she answered. "I have had worse cases than that. When shall I expect your sister, sir?"

Bambino promised to bring her round that evening, and took his departure.

Later in the day he made his reappearance with Adéle, who evinced no attachment for him and seemed only to care for being alone.

For hours she would talk to herself and occasionally press her hands to her head, as if it hurt her.

Mme. Vesta Levine had a room at the top of her house prepared for her and detailed a colored woman to wait upon her.

"Beware," said Bambino as he left the house, "how you treat my sister. I shall demand a strict account of you."

The madame smiled scornfully, for she glanced from the swarthy Italian to the fair-haired daughter of France, and she knew in one instant that they were not related.

"Sir," she replied, "your 'sister' is perfectly safe in my hands, and when you require her I shall be perfectly ready to deliver her."

Bowing politely the Italian took his leave, feeling that Adéle was in good hands, and that he could find her whenever he wanted her.

While returning to the hotel at which he was staying, he beheld two gentlemen walking together on Broadway.

No sooner had he seen them than he drew his breath quickly and drawing his hat over his brows, darted into a doorway to allow them to pass, without perceiving him.

It was Jack Harkaway and his friend Harvey.

"We must hurry," exclaimed Jack, "or we shall be late for Miss Van Hoosen's reception, and you do not know how my heart longs to see that girl once more."

Harvey laughed lightly.

"It seems to me," he replied, "that you are very much smitten in that quarter."

"I don't mind acknowledging it," said Jack. "She is just about the sweetest, prettiest, most charming young lady that I ever met in all my travels."

"So she is," answered Harvey. "She is worthy of you and you of her."

"If it had not been for the superlative attraction that she has for me I should not be here now."

"Well! You can congratulate yourself on one thing."

"What is that?"

"You have cut Lord Maltravers out of the game entirely. He has no show now. Ha! Ha!" laughed Harvey.

"Ha! ha!" laughed Jack. "You are right there, but the fellow is dangerous."

"Yes, indeed."

"Fancy his sending a fellow to assassinate me. It was lucky I got the best of him."

"Between you and the fishes of the Atlantic there cannot be much left of the villain," remarked Harvey.

This conversation was distinctly audible to Bambino, as the two young men had paused to light their cigars.

"We shall see!" muttered the crafty Italian. "Let those laugh who win."

At this moment an elderly gentleman, passing by in the dim light of the evening, drew out his pocket-handkerchief; and, in doing so, a large wallet fell on the sidewalk.

He did not notice his loss.

Bambino, however, saw it, and a sudden idea came into his head, upon which he did not hesitate to act.

Starting rapidly forward, he picked up the wallet, and pushing against Jack, dropped it into the pocket of his overcoat.

"Here, you, sir!" exclaimed Jack. "Where are you coming to?"

"Beg pardon," answered Bambino, in a gruff voice.

"Don't do it again, that's all," rejoined Jack. "There is lots of room for both of us."

Bambino retired as quickly as he came, and walked after the elderly gentleman who had lost the wallet.

"Sir," he exclaimed, touching him on the shoulder.

This man was a merchant connected with the Produce Exchange, very wealthy, but very mean.

"I've nothing for you," replied Mr. Cobb, for that was his name.

"I want to speak to you."

"Not to-night, my good fellow. I can't give anything to tramps and beggars."

"Listen a moment," persisted Bambino. "Have you lost anything?"

Instantly Mr. Cobb's hands dived into his pockets, and a look of alarm stole over his face.

"Why, bless me, yes, my wallet!" he said. "Have you seen it?"

"Did it contain anything valuable?"

"I should say it did. Valuable! What's the man talking about? Where is it? Tell me at once, or I'll call the police and have you arrested."

Bambino pointed to Harkaway, who was only a few yards ahead.

"Do you see that person?" he asked.

"Which one—there are two together?"

"The stout one. It is he whom I saw take your wallet from your pocket."

"Then he is a thief?"

"Precisely," replied Bambino. "Good-evening. I hope you will recover your property."

Lifting his hat politely, he turned down a side street, leaving Mr. Cobb to go after his money.

Harkaway was perfectly unconscious of the trick that had been played upon him.

As for Harvey, he was a little uneasy.

"Jack," he said, "did you notice the face of that fellow who pushed up against you?"

"Not distinctly; why?" replied Jack.

"I did, and the features reminded me of that Italian scoundrel of whom we were talking."

"Bambino?"

"Yes. The hired assassin of your sworn enemy, Lord Maltravers."

"Absurd!" exclaimed Jack. "The fellow perished at sea. We know that very well."

"Never mind; the face haunts me."

"You shouldn't indulge such silly fancies, Dick. I tell you the rascal is as dead as a doornail," replied Jack.

Just then, Mr. Cobb rushed up and seized Harkaway rudely by the arm.

"Hello!" exclaimed Jack. "What's the matter with you? Has every one got a mania for jostling me to-night?"

"My wallet, my wallet!" cried Mr. Cobb.

Jack shook off his grasp and drawing himself up proudly looked him sternly in the face.

"My good sir," he said, "be kind enough to explain yourself."

"You have stolen my wallet. I saw you do it."

This was a stretch of imagination on the part of the produce merchant, but he relied on what Bambino had told him.

"Do I look like a—a thief?" inquired Jack, not knowing whether to get angry or not, and feeling inclined to regard Mr. Cobb as a harmless lunatic.

"No," admitted the merchant, "but gentlemanly thieves are the most dangerous."

Jack turned inquiringly to Harvey.

"Dick," he exclaimed, "ought I not to knock this man down?"

"Under the circumstances, you would be justified," replied Harvey. "But, my dear boy, he is old and we should respect old age."

"True. Pass on, sir, and do not presume to annoy me any more with your ridiculous charges," said Jack.

"My money. I want my money, robber. You shall not escape me thus," persisted Mr. Cobb.

Again he laid his hand on Jack, who this time flung him violently against the window of a store.

A small crowd of idlers began to collect, and the attention of one of the Broadway squad was arrested.

"What's all this?" asked the officer, coming up.

"Arrest this man," cried Mr. Cobb.

"What for?"

"Robbery. I charge him with having stolen my wallet, containing a large sum."

"Who are you?"

"Richard Cobb, of the firm of Cobb and Co. Every one knows me in South street."

The officer seized Jack by the elbow.

"I arrest you," he said. "Come along."

"Allow me to explain," exclaimed Jack.

"You can do that at the station."

Jack shrugged his shoulders.

"This is a queer country," he replied; "yet I make it a rule never to resist constituted authority."

"You wouldn't find it much use if you did," answered the officer, swinging his locust club.

Harvey was much annoyed.

"Let me assure you, policeman," he said, "that you have made a mistake."

"Can't help it," was the stolid reply.

"This is my friend, Mr. Harkaway, of England. We are stopping at the Fifth avenue Hotel."

"I guess the pair of you will stop somewheres else to-night," answered the policeman, smiling at his own joke.

It was useless to argue the point, and the officer conducted his prisoners to the station, where Mr. Cobb made his charge.

Jack indignantly denied the accusation, and demanded to be searched.

Imagine his dismay, when the searchers produced the missing wallet from the pocket of his overcoat.

"That's mine!" cried Mr. Cobb, exultantly. "What did I tell you?"

"Lock 'em both up," said the captain.

"I will send for the British Consul," exclaimed Jack. "This is some infamous plot."

"Bambino," muttered Harvey.

"Right, Dick; your eyes were better than mine. I ought to have known that the fellow was never born to be drowned," replied Jack.

"Put them in different cells," continued the captain.

They were conducted below and locked up, feeling very indignant, but unable to help themselves.

The charge looked very grave against them, and Harvey was as much implicated as Jack, because he was regarded as an accomplice.

Mr. Cobb promised to appear in the morning, and went home.

As he left the station he did not perceive a man who was hiding in the shadow of a house.

This was Bambino, who had watched the arrest, and finding that the game was securely bagged, turned away with a chuckle.

"Five years in State's prison for highway robbery," he muttered, "will please his lordship."

Repairing to a telegraph office, he sent the following dispatch by cable to Maltravers:

"Come over as soon as you can. The coast is clear. The lady can be yours, as Jack will not be likely to cross your path for some time to come.

"Bambino."

A LOVERS' QUARREL.

Professor Mole was very much surprised at the failure of Jack and Harvey to return to the hotel, and he was still more astonished, when at midnight he received a note informing him of their arrest on a false charge of robbery.

He at once proceeded to the station and had an interview with them, and afterward procured bail in the person of the proprietor of the hotel.

The next thing was to see Mr. Cobb, who, now that his money was recovered, was in a happier frame of mind, and being satisfied of Harkaway's respectability, consented to withdraw the charge.

How the money got into Jack's pocket it was not easy to explain, and the affair remained a mystery.

It was unfortunately necessary for Harkaway to appear in court, but on Mr. Cobb's application he was discharged.

The case, however, was reported in the papers; and Jack, to his mortification, read a paragraph entitled:

"SINGULAR CHARGE AGAINST AN ENGLISH GENTLEMAN.

"Mr. Jack Harkaway and Mr. Richard Harvey, two English gentlemen of means and respectability, residing at the Brevoort House, were charged at the Jefferson Market police court with stealing a wallet containing three thousand dollars in cash and securities, from the person of Mr. Cobb, a well-known member of the Produce Exchange. The money was found on Mr. Harkaway, but Mr. Cobb, feeling assured that there was a mistake somewhere, refused to prosecute and withdrew the charge, whereupon the prisoners were discharged."

This was intensely annoying to Jack, because it stabbed his reputation and cast a slur upon his honor.

There was no possibility of explaining the matter, and he felt that his character was blackened, though his friends did not attach the importance to the occurrence that he did.

The villain, Bambino, had not succeeded in his purpose, which was to put Jack out of the way in a prison, so as to make the coast clear for his noble employer.

Yet he had inflicted a wound on a most sensitive mind, and he chuckled inwardly at the chagrin which he knew Harkaway must suffer.

With cat-like stealth he watched and waited for an opportunity to deal him another blow.

The effect of the publication above referred to was soon apparent.

Jack determined to show himself everywhere, for he thought that to hide himself would be to tacitly admit that he was guilty and felt ashamed.

Consequently he drove out nearly every day.

Mr. Mole, Captain Cannon and Mr. Twinkle were occupied in searching New York and its vicinity for buffalo; but, much to their disappointment, they could not find any.

The professor prepared an elaborate report for the club which had sent out the expedition, in which he stated: "After a prolonged investigation, I am inclined to think that the buffalo, like the mastodon and the dodo, is an extinct animal, as I can discover no trace of a living buffalo so far, though I am in hopes that when we visit Long Island, which I am told is wild and savage, we may meet with some specimen of this almost mythical beast."

There was going to be a steeple-chase at Jerome Park, and Jack sent Miss Van Hoosen an invitation to ride to the grounds.

This led to the first severe mortification he received, after the report in the papers, for Lena refused in the following brief note:

"Miss Van Hoosen presents her compliments to Mr. Harkaway, and begs to thank him for his invitation, which she is reluctantly compelled to decline."

On receiving this, Jack showed it to Harvey.

"Look at that, Dick," he exclaimed, "and tell me what is the meaning of it."

Harvey read it, and replied, "It is laconic enough, and it means, simply, that the lady will not go."

"What would you do, under the circumstances?"

"Call upon her and have an explanation."

"I shouldn't be surprised, if she has seen that paragraph about Mr. Cobb's money."

"More than likely."

Jack bit his lips with vexation and his face reddened.

Without losing any time he visited Lena, and was shown into the reception-room.

Presently Lena entered, looking more than usually sweet and charming.

There was some slight embarrassment in her manner, as she held out her hand and requested him to be seated.

"I am so sorry you cannot come with us," he said.

"So am I," she replied. "But I am glad to have an opportunity of explaining. There is no gentleman of my acquaintance whom I esteem more than I do you."

Jack bowed politely, and felt that he could have laid down his life for her, for saying those words.

"My brother," she continued, "has read something about you in a journal, and he says I ought not to receive your visits. I feel that there must be some mistake. If you could only see my brother and explain—"

A tall gentleman, a few years older than Jack, entered the room at this moment.

"No explanation is necessary," he exclaimed.

Jack flushed indignantly.

"I presume," he said, "I have the honor of addressing Mr. Alfred Van Hoosen?"

"That is my name," replied the new-comer, stiffly.

"And the brother of this lady?"

"Precisely, sir."

"In that case, your relationship prevents me from taking the notice of your words which I otherwise should."

"Oh, sir," said Alfred Van Hoosen, as he smiled sarcastically, "pray do not let that stand in your way."

"I was simply desirous of assuring your sister that there was absolutely no foundation for the report to which she alluded."

"The case speaks for itself."

"Am I to understand that you do not consider me a proper person to visit at your house?"

"That is what I intended to convey to you, and I have to thank you for saving me the trouble of expressing myself."

Jack turned to Lena, regarding her almost with an imploring glance.

"Do you concur in your brother's opinion?" he asked.

She would not trust herself to speak, but inclined her head.

Burning with mortification, Jack quitted the house with despair in his heart, for it seemed as if Lena was lost to him forever.

In order to regain her good-will it would be necessary to satisfy her brother, and as he would listen to no explanation, this course seemed impossible.

For some time he was inconsolable, but he determined to go to the race all the same, hoping that he might at least see Lena there.

It was a lovely day, and all the wealth and fashion of New York was hastening toward the Park.

On Eighth avenue they passed an open carriage, in which were seated Miss Van Hoosen and her mother.

In spite of his dismissal of the day before, Jack ventured to raise his hat, but Lena did not bow, though he fancied her eyes appeared to seek his.

"Fine girl that," remarked a gentleman who sat by Jack. "You appear to know her."

"Yes," replied Jack, "I met them in Paris—that is—her mother and herself."